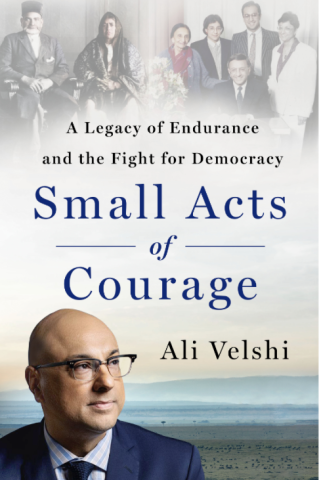

A moderated conversation between Ali Velshi, MSNBC news anchor and author of the book, "Small Acts of Courage: A Legacy of Endurance and the Fight for Democracy," and Dr. Peniel Joseph, founding director for the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy and the Barbara Jordan Chair in ethics and Political Values. Lunch provided. Registration required.

About Betty Anderson

The Betty Anderson Speaker Series is named in honor of Betty Anderson. Betty’s son Art is a graduate of the joint LBJ School and UT School of Law program and son Dale received his M.D. from U.T. Southwestern Medical School.

From the 1960’s to the 1990’s Betty was on the forefront of social justice issues impacting children, lower income and women’s rights from the grassroots level to leading state agencies and national nonprofits. Few Texans have made such significant contributions to the health and well-being of the State’s residents.

We all see things that we would like to change, but when Betty identified a need for change, she did something about it. She created organizations, served on boards, wrote letters to the editor, and visited with elected officials frequently. The grace with which she debated issues allowed her to share her perspectives with officials who, regardless of their views on the subject, welcomed her well-researched and well-presented input.

At the local, state and national levels, Betty trained boards and conducted public policy workshops and lobbying training programs. She served on governmental advisory committees for maternal and child health, day care, reproductive freedom of choice, equity in education, sexual harassment, peace, aging and disabilities. She spearheaded coalitions to put the basic health and human needs of people first in legislative budgets. Betty's work with public groups helped create a political climate for reform measures such as property tax reform, removing the specific dollar amount for welfare spending from the state constitution, child care legislation, indigent health care reform and education reform.

Her father Henry Price was a Methodist minister and mother Irene was a math teacher. In accordance with Methodist Church tradition, Rev. Price moved to a new church appointment throughout Central Texas every few years. Betty attended at least eight different elementary and high schools. Constantly moving to a new town and school made her adaptable to change and helped her to form friendships quickly. Her parents also instilled a sense of duty to serve others. At the age of 40, Rev. Price volunteered to serve overseas in World War II as a chaplain.

Betty received her B.S. at the University of North Texas (then NTSU) in 1954. There she was highly influenced by the chaplain and staff at the college’s Wesley Foundation who were focused on social justice issues.

Following graduation, she taught at Arlington High School where she met John Anderson who was a professor at Arlington State (now UTA). She married John the night before he was shipped overseas to serve in the U.S. army in Germany. They later moved to Lubbock where John was named a professor of biochemistry at Texas Tech University.

After moving to Lubbock, Betty quickly got involved with a support group of smart, energetic, socially compassionate women, many of whom were either on faculty or spouses of Tech faculty members. She willingly joined and started working in a number of civic and charitable organizations, and her support group honed her organizational and oratory skills.

One of her loves was the League of Women Voters where she served as the local and state president, as well as on numerous national committees. She received the 2003 League State President's Award and the National League's Voters Education Fund Leaders Award.

Another passion was the American Association of University Women where she served as the local and state president and on the national board. She was named an AAUW Woman of Distinction, and the Lubbock branch was renamed in her honor.

Recognizing the social and economic disparities in Texas and nationally Betty's energies in the 1960's and 1970's focused on improving the lives of all women. She was outspoken in her support of equal rights, not a particularly popular position in West Texas. In the late 1960's and early 1970's passage of an equal rights amendment (ERA) provided a rallying point in the years after attaining woman's suffrage. Betty joined Texas pioneers such as Hermine D. Tobolowsky, Sissy Farenthold, Ann Richards and Barbara Jordan in obtaining overwhelming support of the Texas Equal Rights Amendment to the Texas Constitution. Texas also voted to approve the national ERA to the U.S. Constitution but it failed to obtain the approval of the necessary 38 states to ratify.

In 1973 Betty went back to college for her master's degree. The subject of her master's thesis was on a woman's right to an abortion. Texas Tech named her a distinguished alumnus in 1986. She helped found and also served on the boards of the Rape Crisis Center and South Plains Aids Resource Center.

In 1989 she helped lead a group of Texas religious leaders at the March for Women's Equality and Women's Lives in Washington, D.C. The marchers were protesting the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Webster v. Reproductive Rightswhich rolled back the Roe v. Wade abortion protections for women. At the time, it was the largest march on D.C. since Martin Luther King's 1968 "I have a dream" speech.

In the 1980s, as chair of the Governor's Commission for Women, Betty was instrumental in developing a legislative women and children's agenda for the Texas Legislature with the feminization of poverty, women's economic justice and pay equity as issues of great concern. In the 1990s, she chaired the Texas Maternal and Child Health Advisory Committee and was a member of the Texas Commission on Children and Youth. At the national level, she organized AAUW visits to every Texas congressional office for the passage of the Family and Medical Leave Act.

Betty's interest in health care was sparked by the League of Women Voters of Texas Education Fund and the Texas Department of Human Services Foundation National Health Care Debates in 1986, for which she served as a moderator. From 1988-92, she chaired the national Health and Welfare Committee of the United Methodist Church. For the following two years, she lobbied on health care issues in Washington, DC.

Betty served on numerous local and state committees and personally assisted the homeless, aged, disabled and children. Her state governmental appointments included the Texas Commission on Children and Youth, the Texas Urban Planning Commission Health Committee, the Texas Department of Human Services Aged and Disabled Committee which she chaired and the Adult and Protective Services Advisory Committee. She helped to create and was a board member of the Texas Center for Public Policy Priorities (now Every Texan) in 1994.

Betty's local governmental activities include the South Plains Regional Workforce Development Board, Airport Zoning Board, South Plains Area Agency In Agency Advisory Council, Urban Renewal Board, Community Development Block Grant Advisory Committee, Planning and Zoning Commission, Lubbock Independent Bond Steering Committee, LISD Smooth Transition Committee for Degradation, Lubbock Area Children's Legislative Agenda, Children's Advocacy Center, Lubbock Interfaith Hospitality Network for Homeless Families and more than 50 other West Texas agencies and nonprofits.

In 1983 she helped to found the South Plains Food Bank which started in a 5,000 square foot warehouse with 28 agencies. It grew to partner with 170 agencies serving more than 9 million meals per year. In the 1990's SFFB developed the Breedlove Dehydration Plant, providing food for humanitarian agencies around the world. John Anderson applied his biochemistry knowledge to help operate the plant in its early years.

The 1996 federal budget passed by Congress contained $24 billion for health insurance for children in low-income families. Texas had 14% of the nation's uninsured children ("CHIP"). Under the program Texas would receive 75 cents from the federal government for every 25 cents allocated by the state. In 1997 Betty was the West Texas liaison for Texans Care for Children which was formed to persuade state law makers to fully fund programs for needy children. She helped 15 agencies in lobbying Texas legislators and wrote letters to the editor to encourage public support: "By ensuring Texas kids today, we can build a better tomorrow. Be a voice for children: It's time for all of us who care about children to stand up and be counted." Texas reached full enrollment of 428,000 kids within one year.

Betty became a board member of the Texas Committee for the Humanities and Public Policy (now Humanities Texas) and served as chair in 1981. Under her leadership TCH established a task force on the humanities in public schools which issued a report that resulted in enhanced elementary and secondary education and recognized outstanding teaching in the humanities. She led the effort to approve a large grant to the Texas Foundation in Women's Resources which resulted in a collaborative effort to launch a major touring exhibit on Texas women's history.

At the international level, Betty received the International Venture Club's Mae Carvel Award for Women Helping Women in 1998 in Toronto. She was a delegate to the International Women's Year Conference in 1977. Betty was a moderator at the Conference on the International Women's Decade and Beyond in New York. In addition she helped lead seminars at United Nations and Women and World Development Seminars from 1986-90.

Betty served her faith as a member of St. John's Methodist Church in Lubbock where she was an elected delegate to Annual and General Conferences and served on the Board of Church and Society and the National Health and Welfare Committee of the United Methodist Church. In 1993, Betty received the SMU Perkins' School of Theology Woodrow B. Seals Laity Award for Service to Church and Society.

In 1998 she served on a national committee of the Methodist Church concerned about the lack of inclusivity language in the hymnal and other church material. In October 1981 the 9.6 million member Methodist Church looked for ten persons to serve on a committee to promote language as both male and female. Betty stated that "it's important to look at the language of God because it does affect the way we view the image of God". Her efforts resulted in the adoption of a hymnal that was more sensitive to the concerns of women, minorities and the disabled.

Betty had many interests besides activism – politics, education, government, and the arts, for instance. She and John travelled around the world and frequently went on trips with Lubbock friends. Annually they would go to Santa Fe during the summer opera season. One story illustrated the way she adapted her musical interest to West Texas. When she and John moved to Lubbock she accepted engagements to perform on the harp, which she played beautifully, and the Andersons bought a pickup to accommodate the harp. Pickups were common in West Texas but John and Betty's vehicle was the only one with a harp in the back.

Betty's main challenge was turning down new opportunities to help the underrepresented in our society. At one point in time she was asked to be on the board of a national organization. After writing down the names of all of the organizations she was actively involved her list exceeded 35 different groups. Even Betty had to say "No" sometimes. If there were a way to clone Betty Anderson the world would be a much better place.

Following her death in 1998, the Texas House of Representatives passed a lengthy commemorative resolution in Betty's honor. It concluded with the following statement: "Though it is impossible to gauge the full effect of a person's life, some individuals leave their unmistakable mark on the world as they move through it, and Betty Price Anderson's legacy of compassion, vision, and commitment to her fellow Texans will be cherished for years to come." Truer words were never written.